Carrying The Weight Of JFK's Casket How Much Weight Do Pallbearers Carry

Fifty years ago, when Douglas Mayfield was one of President John F. Kennedy’s pallbearers, the San Diego native was too busy to grieve.

U.S. Army Specialist 4 Mayfield escorted the body to its autopsy; to the White House for one last night; to the Capitol rotunda, where mourners filed past; to a cathedral for the president’s funeral; and finally, as drummers beat a measured tempo, to a plot in Arlington National Cemetery.

Then the soldier collapsed in his barracks, pursued by sad sounds.

“Those drumbeats, I’ll tell you,” Mayfield said. “That presidential drumbeat was so different and haunting. For days, I could hear those drums.”

Kennedy’s motorcade through Dallas was struck by a fusillade of bullets a half century ago, yet this distant event remains a vividly-recalled watershed in our history. This week, the assassination will be examined in docudramas, books and news stories. Conspiracy buffs spin theories about why Lee Harvey Oswald — and others? — murdered our youngest elected president. Historians wonder if our nation would have charted different paths — in Vietnam, in civil rights — if Kennedy had left Texas alive.

All Americans of a certain age can recall what they were doing, where they were and how they felt when the news hit.

In the Army and just 21 at the time, San Diego native Douglas Mayfield was a pallbearer at the funeral of President John F. Kennedy 50-years-ago. Video by Howard Lipin

Here’s what a 21-year-old from Encanto felt, when his job suddenly thrust him onto the world stage: incredible tension.

“The pressure was always on us,” Mayfield said. “We were thinking ‘Just don’t screw up.’ The world was watching.”

JFK in San Diego: 50 years later

Hero in the back

In ceremonies that stretched across four chilly fall days, Nov. 22-25, 1963, the nation bade farewell to its slain leader. Throughout this somber pageant, Mayfield stood near the edge of the drama. He never wanted to be in the spotlight and, even today, shrinks from revisiting these scenes.

“I’ve always been the type who likes to sit in the back row, furthest away from the limelight,” he said last week. “I didn’t even go to the prom — I was too shy to ask a girl out.”

1/17

Sen. John F. Kennedy waves to crowd during campaign visit to San Diego. November 2, 1960. (Thane McIntosh/U-T San Diego file photo)

2/17

June 6, 1963 -- Marine Recruit Depot sergeant shows President Kennedy the latest in training casuals on model recruit. UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

3/17

June 6, 1963 - President Kennedy watches recruit get four-minute haircut in eight-chair barber shop of Marine Corps Recruit Depot. UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

4/17

June 6, 1963 - President John F. Kennedy greets crowd through the fence upon his arrival at Linbergh Field in San Diego, California. Photo: C.R. Learn/UT file photo (C.R. Learn/U-T San Diego file photo)

5/17

June 6, 1963 -- President John F. Kennedy waves to crowd during parade route on El Cajon Blvd. in San Diego, California. Photo: UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

6/17

June 6, 1963 - San Diego. President Kennedy on 1900 block of El Cajon Blvd in San Diego, California. U-T San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

7/17

June 6, 1963 - President Kennedy shakes hands with a well-wisher in crowd at San Diego State College. UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

8/17

June 6, 1963 - President Kennedy shakes hands with a well-wisher in crowd at San Diego State College. UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

9/17

Sen. John F. Kennedy gives speech in front of the Grant Hotel during campaign visit to San Diego. Standing next to him is Sen. Hugo Fisher (D-San Diego). November 2, 1960. Photo: Joe Flynn/UT San Diego file photo (Joe Flynn/U-T San Diego file photo)

10/17

Sen. John F. Kennedy gives speech in front of the Grant Hotel during campaign visit to San Diego. November 2, 1960. Photo: Thane McIntosh/UT San Diego file photo (Thane McIntosh/U-T San Diego file photo)

11/17

Democratic presidential candidate Senator John F. Kennedy waves to crowd during parade in San Diego, California, November 2, 1960. UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

12/17

John F. Kennedy, shown during a parade in San Diego, November 2, 1960, called a generation to serve the nation in his 1961 inaugural address. UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

13/17

February 5, 1964 -- Douglas A. Mayfield of San Diego, an honor guard casket bearer at President Kennedy’s funeral, points to himself in a picture. Photo: Ted Winfield/UT file photo (San Diego History Center / Union-Tribune Collection)

14/17

Democratic presidential candidate Senator John F. Kennedy gives speech at Lindbergh Field in San Diego, California, November 2, 1960. UT San Diego file photo (U-T San Diego file photo)

15/17

November 24, 1963 - The Rt. Rev. Msgr. John L. Storm speaks during interfaith memorial service for JFK at Westgate Park in San Diego, California. Photo: C.R. Learn/UT file photo (San Diego History Center / Union-Tribune Collection)

16/17

More than 5,500 attended an interfaith memorial service for slain President Kennedy in Westgate Park on Nov. 24, 1963. SAN DIEGO UNION STAFF PHOTO BY C.R. LEARN (San Diego History Center / Union-Tribune Collection)

17/17

November 22.1963 -- People on San Diego downtown streets react upon hearing the news that President John F Kennedy was assassinated. San Diego History Center / Union-Tribune Collection (San Diego History Center / Union-Tribune Collection)

Mayfield, though, is no wimp. A Lincoln High graduate, he was drafted into the Army, spending most of his two years of active duty in Virginia. As a San Diego police officer in 1971, he rescued a man from a burning building. The day receiving the department’s lifesaving medal, he responded to an altercation on Ivy Street and was stabbed in the chest. Recovering from that wound, he rose to detective’s rank.

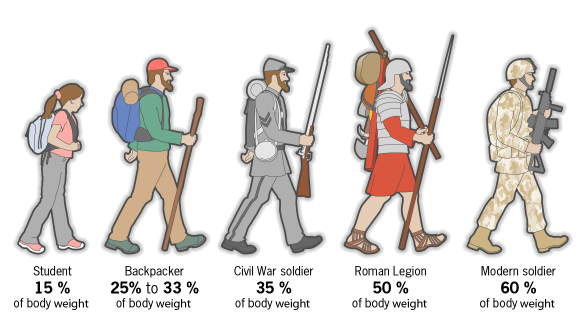

He retired in 1993, suffering from worsening back pains. The detective traces this ailment back to his pallbearing days, saying it was exacerbated by carrying Kennedy’s casket — an episode that was news to his police colleagues.

“I never told my partner,” Mayfield said. “I didn’t tell anybody.”

“He didn’t tell me,” said Gretchen Mayfield, his wife. “I found out the first time when someone sent him a letter.”

Over the decades, hundreds of strangers have written to Mayfield. Some ask for his account of Kennedy’s funeral; many request an autograph; one boy quizzed Mayfield about the size and material of his dress uniform gloves.

Authors, too, have sought him out. He makes brief appearances in William Manchester’s 1967 “The Death of a President;” “Four Days in November,” a 2003 reprint of The New York Times’ 1963 coverage; and “On Hallowed Ground,” Robert M. Poole’s 2009 history of the Arlington National Cemetery.

While he’s been interviewed about Kennedy several times, he’d rather talk about his travels, his eight grandchildren, or the show cars he’s rebuilt. The walls of his El Cajon house are lined with photos of a 1923 Model T hot rod, a ’29 Model A, a ’34 Ford Phaeton, a ’42 Ford convertible and other classic vehicles — and only two photos from those tragic days in November 1963, when his skills as a pallbearer were tested to the utmost.

Mayfield had been part the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment, the “Old Guard,” the Army’s longest-serving unit. In 1962 and early ’63, his duties with the presidential honor guard had involved a few White House functions — Jacqueline Kennedy, the first lady, once engaged him in small talk — but most of his time was spent in Arlington on burial details.

At first, Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, seemed like an ordinary day. The pallbearers had finished their shift when Mayfield noticed that detail’s bugler had a transistor radio at his ear and a dazed expression on his face.

“The president has been shot!” the bugler gasped.

“Now,” Mayfield remembered thinking, “it was going to be all hell.”

Bearing the weight

Back at the barracks, Lt. Sam Bird took charge. Then just 23 years old, Bird commanded a team of pallbearers representing every branch of the U.S. military. Their duty: Convey Kennedy’s casket to all ceremonies, public and private.

This job’s challenges began to emerge that night at Andrews Air Force Base near Washington, D.C. When Air Force One landed, a general aboard the plane refused to relinquish the casket to the honor guard. Secret Service agents struggled with their heavy burden until finally, with help from pallbearers, they loaded it onto an ambulance.

That vehicle drove toward Bethesda Naval Hospital; Bird’s team gave chase in a helicopter. Landing outside the hospital, the pallbearers removed the casket from the ambulance and brought it into a private room. There, an autopsy was performed on what had been — less than a day earlier — the world’s most powerful figure.

Early on Saturday, Nov. 23, the body was released and was transported into Washington. The pallbearers removed their precious cargo outside the White House around 4 a.m. and began marching through darkness, toward the Executive Mansion.

“All of a sudden,” Mayfield said, “lights and cameras illuminated the place like it was daylight.”

As the media’s flashbulbs popped, the six pallbearers walked toward the White House, struggling to uphold their 1,300-plus lbs. responsibility.

Mayfield, second from left, helps carry President Kennedy’s casket.

“With every step,” Mayfield said, “the casket was going a little bit further down.”

“Lieutenant!” Mayfield whispered.

No response.

Ignoring protocol, Mayfield turned his head and looked at Bird, three paces behind the casket.

“Lieutenant!”

Also breaking protocol, Bird stepped forward and lifted the casket, safely bringing it inside.

The next day, the lieutenant reinforced his team with two additional pallbearers.

Midnight rehearsal

The additions were welcome, as the pallbearers were working round-the-clock. When they weren’t carrying Kennedy’s casket, they were scrambling to master their duties, aware that every action had to be crisp and flawless.

They knew, for instance, that they would have to ascend the Capitol’s steep steps — “it looked more like a wall than steps,” Mayfield recalled — and deliver the casket to the rotunda.

On the night before that mission, Bird assembled his team at Arlington for a test run. Hoisting a practice casket packed with sandbags and topped with two sturdy GIs, the pallbearers climbed the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier’s steps. This midnight rehearsal went off without a hitch, as did Sunday morning’s actual ascent of the Capitol steps.

On Monday, Nov. 25, the pallbearers descended the Capitol steps, then placed the casket on a caisson and accompanied it to St. Matthew’s Cathedral. After the funeral Mass, the pallbearers exited the church and fastened the casket to the caisson for the three-mile trek to Arlington.

Mourners had mobbed the Capitol and the cathedral, Mayfield remembered, but larger throngs lined the streets of Washington for this final journey. He did not see John F. Kennedy Jr. — “John-John” — saluting his father’s casket. But he noticed the silence, broken only by a drum corps rapping out a slow, sad beat.

At the grave site in Arlington, the pallbearers faced another challenge. Lifting Old Glory off Kennedy’s casket, they had to fold it into a tight triangle that showed nothing but a blue field and white stars. Because maneuver requires precise timing, the mixed band of pallbearers had devoted hours to practice.

“Usually,” Mayfield said, “you spend about six months training how to carry the casket and fold the flag. We had two days.”

That was enough. Mayfield delivered the perfectly-folded flag to Arlington’s director, who presented it to the widow.

Then it was over. The new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, Charles de Gaulle of France, Ethiopia’s Haile Selassie and other dignitaries filed out. Mayfield, who had only six or seven hours of sleep across those four days, went to his barracks to rest.

“I was tired,” he said, “I was sore, I was ready to come home.”

Two months later, he did. He built a new life that makes few references to November 1963. Inevitably, though, a call or a letter stirs memories of those days and the steady, mournful sound of those drums.

“I was involved in several large ceremonies at Arlington, but nothing compared to this one,” Mayfield said. “I was proud of the fact that I was involved in the most famous funeral in history.”

peter.rowe@utsandiego.com • (619) 293-1227 • @peterroweut

0 Comments

Post a Comment